As Iran’s Currency Collapses, its Housing Crisis Explodes

Steven Terner*

ACIS Iran Pulse no. 109 | July 26, 2020

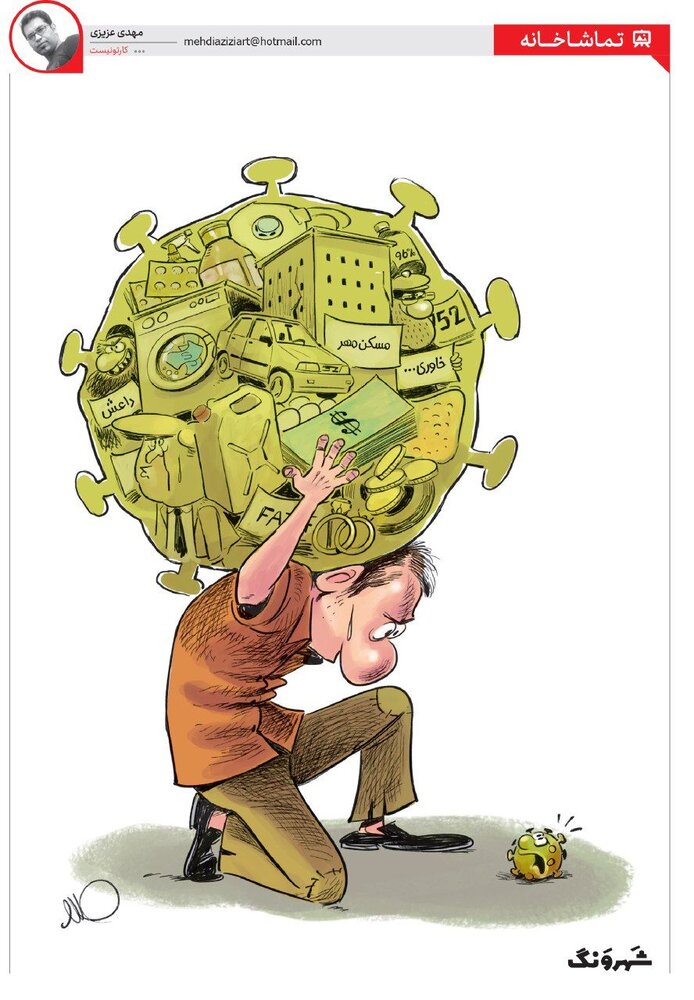

The value of the Iranian rial collapsed over the past three months due to the combined impact of corruption, mismanaged economic policy, international sanctions, and the Covid-19 global pandemic. At the same time, the price of homes in Iran has skyrocketed. With fewer people able to purchase property, more are forced to rent a residence. The rate at which these changes are occurring is exacerbating a housing crisis that has persisted for decades. Resolving this crisis will require widespread economic recovery, as well as a fundamental political reorganization, neither of which are likely in the near future.

Statistics published by the Real Estate Union show that in the month of Khordad (May 21 to June 20) this year, roughly 43,000 new rental contracts were signed nationwide; of these 10,000 were in Tehran, primarily in the city’s relatively wealthy northern neighborhoods. Nationally, this represents a 27% increase in rental contracts over the previous month, and a 10% increase in the capital. During this period, the average price per square meter in Tehran increased by more than 2 million toman (nearly USD 500) from 17,006,000 to 19,071,000 toman (more than USD 4,500) per square meter. However, these numbers are not extraordinary in Iran.

Housing economist Mehdi Sultan Mohammadi explains that over the last 27 years, home prices have increased by an average of 19.5% annually, and rental prices have increased an average of 21.5% annually. At this rate, he says, an Iranian who is currently 25-years-old will be able to own a home by the time he is 70, at the soonest. Reasons for the rapid, consistent increase in prices are an insufficient supply of homes on the market, and rampant inflation.

Supply and Demand

Rising demand steadily pushes the prices of available properties upward, making them less affordable. Several programs are already being implemented to address this aspect of the crisis. In August 2019, President Hassan Rouhani announced his National Housing Action Plan, initially intending to build hundreds of thousands of new housing units across the country. More recently, he promised to build one million new housing units. The Minister of Roads and Urban Development, Mohammad Eslami, who is overseeing this plan, further explained that 800,000 of these units will be built in cities and 200,000 in rural areas. Some will be part of the Mehr Housing Project, a development plan launched by the Ahmadinejad administration in 2009, which remains incomplete.

On June 16, the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development promised that the Mehr developments will have water and electricity by the end of the year. In addition, large companies are being urged to build housing to rent to their employees. These development programs, and others like them, face numerous obstacles, including a lack of capital, delays caused by the global pandemic, and the construction of requisite infrastructure, such as roads, utility grids, etc. to sustain the new developments. Bureaucratic red tape also dis-incentivizes construction companies from becoming involved in housing projects.

Alternatively, rejuvenating old, shabby districts in cities by renovating old homes and putting them back on the market is a more cost-effective way to create new housing opportunities because the infrastructure and communities already exist. Eslami has also taken umbrage at the estimated two million vacant residential units around the country, many of which are second homes. If added to the market, they also could bring prices down, at least theoretically, and provide housing for prospective tenants or new owners. Therefore a plan to tax the owners of homes left vacant has been proposed. According to the plan, a vacant home would not be taxed if left empty for up to one year. It would then be taxed 50% of the calculated rent for the second year left vacant, and 100% for the third year. However, the Tax Authority is concerned about the difficulty of identifying if a property is vacant and for how long it has been unoccupied. A comparable plan is also in the works for vacant lots in metropolitan areas that could be developed for new housing.

It is important to note that these taxes are not intended to be a source of significant revenue for the government. Rather, they are aimed at convincing absentee owners to put their properties on the market, for either purchase or rental. It remains to be seen, though, how many of those who might have to pay these fees will be deterred by them.

Inflation

The effectiveness of the tax plan is uncertain because the rapid inflation in Iran means that home prices have risen more quickly than the value of people’s liquid capital savings and salaries. Therefore, individuals with significant means purchase real estate as an investment vehicle capable of protecting the value of their capital when rampant inflation devalues their liquid currency. As a result, absentee owners may very well choose to pay a fine rather than to lose the value of their savings by taking them out of real estate.

When wealthy people buy more property, the prices of homes continues to rise, reducing the ability of people who do not yet own homes to purchase, because their money also continues to lose its value due to inflation. They are left with no choice but to rent, thereby losing the equity their money would earn if they had been able to purchase a home.

As Eslami has argued, housing prices in Iran are not governed solely by supply and demand. Rather, inflation is a more significant factor contributing to the housing crisis. Sultan Mohammadi attributes up to 80% of the increase in housing prices to inflation. He therefore believes that although housing is arguably the most difficult issue to address, it is also the one that could have the largest impact on the crisis. However, the ever-present problems of corruption and governmental mismanagement remain obstacles blocking any attempt to curb the rate of inflation.

The Underlying Impediment is Corruption

Farshad Momeni, an economics professor and head of the Institute of Religion and Economics at Allameh Tabatabai University explains that corruption is built around a status quo and requires that it remain in place so it can continue exploiting it. Political rivalries and jostling for influence therefore make the status quo virtually impossible to break.

Without addressing corruption, the actions necessary to get a handle on inflation cannot be taken. As a result, the cost of housing will continue to rise. The working class will not only remain unable to purchase property or pay rent, but will become further impoverished, thereby expanding the wealth gap and ultimately annihilating what is left of the Iranian middle class. Momeni asserts that in order to resolve the housing crisis, the economy itself must be repaired. Doing this, he says, will require a specific plan to be decided upon and implemented consistently over the long-term. He recommends choosing a plan that is known to have worked somewhere else in the world, one that invests in youth because they are the future of the country, and addresses widespread corruption in order to alter the status quo.

He further explains that the current economic policies are focused on expanding the stock market bubble, but that this only furthers expand the wealth gap, because affluent people can purchase large quantities of shares but the working poor cannot. He emphasizes the importance of developing a middle class through investment in technological development, and relying on domestic production, rather than imports, thereby creating jobs and industries. Momeni notes that Rouhani’s foreign policy of detente with the rest of the world could be useful as long as it is part of a broader plan for economic development. However, he says that like the Ahmadinejad administration that preceded it, the Rouhani administration has overseen a decrease in domestic production in many fields, including heavy machinery, which is a necessity for many other industries, including housing.

In addition, as the government seems to be making its policy decisions inconsistently and without a concerted long-term plan, the population has lost faith in its ability to correct the country’s economic ills. In response, many are looking to move their money abroad, leaving businesses at home unable to find investors to develop industries and create jobs, or into real estate, further escalating the housing crisis.

Resolution of the housing crisis can only be considered a long-term goal as it requires wrangling many factors into place, in order for homes to become affordable for middle and working-class Iranians. Although governmental efforts are being made to increase the supply, the rapid rate of inflation will continue to force prices sky high. Unless fundamental political change breaks up the status quo and addresses corruption in a serious way, inflation will not be brought under control any time soon.

Source: Namrhnews, a caricature by Mehdi Azizi

* Steven Terner is a Junior Research Fellow at the ACIS and a doctoral student at the School of History at Tel Aviv University. In 2019, he established IranianEconomicNews.com to examine domestic Iranian economic issues.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@tauex.tau.ac.il, Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

ACIS Iran Pulse No. 109 ● July 26, 2020

© All rights reserved