THE INTERNAL DEBATE IN RUSSIA ABOUT THE NATURE OF TIES WITH IRAN

Number 51 ● 29 May 2012

THE INTERNAL DEBATE IN RUSSIA ABOUT THE NATURE OF TIES WITH IRAN

Roy Bar-Sadeh*

In March 2012, the head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization Fereydoun 'Abbasi-Davani expressed Iran’s readiness to work with Russia on building several additional nuclear reactors in the Islamic Republic (Russian News Agency RIANOVOSTI, 25 March 2012). This announcement was followed by Majlis speaker ‘Ali Larijani’s statement that Russia and Iran “should make an effort to work together to resolve the problems of the Middle East” (Portal ISLAMRF, 26 March 2012). These statements suggest the Islamic Republic’s desire to strengthen its ties with Russia and further develop mutual cooperation based on common interests.

Russia finds this prospect uncomfortable because while Iran signals its desire to improve cooperation between the two countries, Russia faces pressure from Western countries, primarily the United States, to reduce its military ties with the Islamic Republic, and support additional sanctions against Iran in the UN Security Council. In June 2010, Russia voted in favor of a fourth round of sanctions against Iran. Yet in November 2011, Deputy Foreign Minister Gennady Gatilov was quoted saying that extra sanctions "will be seen in the international community as an instrument for regime change in Iran…and the Russian side does not intend to consider such proposals" (BBC News, 9 November 2011). A few months later, in April 2012, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke out against countries threatening Iran and warned that a military attack on Iran could have unpredictable consequences and might well violate international law (RIANOVOSTI, 2 April 2012).

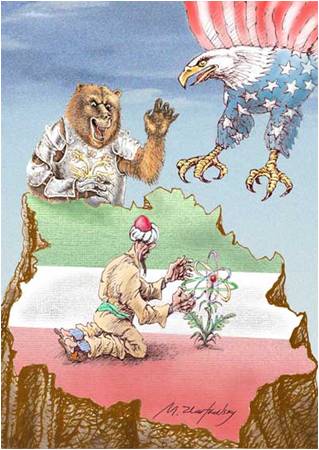

“Peaceful atomic program in Iran” by Mikhail Zlatkovsky, Russia, 4 August 2007, Source:irancartoon.com

The current ambiguity in Russia’s policy toward Iran can be traced back to the bilateral relationship between the two countries following the Islamic Revolution in 1978-9. During the Soviet era, as well as in the post-Soviet era, the Russian political elite debated which policy it should take toward the newly Islamic Republic. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet president at the time, was relatively quick to praise the revolution, and the first prime minister of the Islamic Republic, Mehdi Bazargan, called for the promotion of mutual understanding between Iran and the Soviet Union. However, there was a deep ideologically chasm between the atheist communist regime of the Soviet Union and the Islamic-Shi’i government of Iran that essentially rejected secular Marxist ideology.

Consequently, some members of the Soviet leadership at the time were concerned about a shared border (approximately 1,050 miles; 1,690 kilometers) with a country advocating a religious ideology that was hostile to the Soviet Union and might spread to the Muslim populations of the Soviet Union. Advocates of this position called attention to the spiritual leader of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who issued provocative statements such as “Neither East nor West.” Despite such concerns, the dominant position guiding the Soviet policy during those years emphasized the bitter defeat of the United State’s policy on Iran that was pro-Shah, and believed that the anti-U.S. common ground would be enough to normalize neighborly relations between the Soviet Union and Iran. To this end, the Soviet Union also “recruited” theoreticians and Soviet “Orientalists” who argued that Islam, similar to nationalism, holds both anti- and pro-revolutionary elements that could advance a socialist revolution, and therefore the significant role Islam has played in the Iranian revolution is understandable.

During most of the 1980s, the Islamic Republic, for its part, was cautious in framing its policy toward the Soviet Union. Occasionally, Ayatollah Khomeini referred to Iran’s northern neighbor with derogatory names like “the Red Devil” and “the other Satan.” Members of the Iranian Communist Party (“Tudeh”) were also systematically persecuted by the regime in Tehran. However, compared to Iran’s stance toward the United States, the Islamic Republic’s attitude toward the Soviet Union was perceived by Moscow as quite moderate. Throughout the Soviet war in Afghanistan, the Islamic Republic merely condemned the Soviet Union. Even the Islamic Republic’s response to Soviet aid to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War was met with a relatively mild response: limited economic sanctions against Moscow. Beginning in the mid-1980s, under President Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union increased its trade with Iran, but it was only after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, that a more significant change occurred in relations between the two countries. ‘Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served as speaker of the Majlis at the time, made an official visit to Moscow in 1989, signaling the beginning of closer relation between the two countries.

During the Gorbachev presidency, while reconsidering the Soviet Union’s relationships with other Asian countries, the Russian political elite renewed its debate regarding the nature of its policy toward Iran. The echoes of this debate among the Russian political elite evolved into two different approaches toward Iran:

The first approach, rooted in Russia’s Euro-Asian position, considers Iran to be a vital and strategic ally. Advocates of this approach adhere, for most part, to the nationalistic camp, emphasizing the uniqueness of the Russian civilization, which is neither “Oriental” nor “Western,” and therefore do not consider Russian solidarity with European countries to be a very high priority. The Islamic Republic’s steadfast position in the face of pressure from Western powers, primarily the United States, is appreciated among Russian supporters of this approach toward Iran.

The second approach, which could be called “the bargaining chip” approach, assumes that promoting a temporary alliance with the Islamic Republic might serve Russia in gaining support and concessions from Western countries on other issues. Most of the supporters of this approach wish to increase the status and influence of Russia in the European-Atlantic region (for further reading, see: Dmitry Shlapentokh, Russian Elite Image of Iran, 2009).

In the early 1990s, following the disintegration of the Soviet bloc, the Euro-Asian approach has set the tone for Russia’s policy toward Iran. Under the new regional circumstances, Iran had an opportunity to expand its influence in the former Soviet republics, but abstained from exporting its revolutionary ideology and even refrained from supporting the republics during periods of conflict. For instance, in 1992, Tehran avoided any direct confrontation with Russia, led by Boris Yeltsin (1991-1999), when it supported the pro-Russian coup against the Tajik Islamic government during the civil war in Tajikistan. Iran’s unofficial compliance with Russia’s policy toward the new Islamic republics signaled to Moscow that Tehran was inclined to compromise on its ideological interests in favor of expanding its interests in cooperation with Russia. In 1990s, the Russian government’s leaning towards a Euro-Asian policy, combined with the anarchy that prevailed in Russia during President Yeltsin’s government and the desperate economic condition, set the stage for the Russian-Iranian agreement for the construction of Iran’s nuclear reactor in Bushehr.

Until Vladimir Putin came to power, the Euro-Asian approach continued to prevail among decision makers in Moscow. President Putin, like many other members of the ruling elite of his generation, was influenced by the Euro-Asian approach. However, following the renewal of ethnic tensions between Russians and Muslim populations of the Russian Federation, which had begun late in Yeltsin’s presidency, the Russian elite renewed its internal debate over the nature of the relationship with Iran. The Second Chechen War, which broke out in August 1999 and intensified a few months later with Putin’s emergence, improved the position of those in the Russian elites who supported the “bargaining chip” approach to Iran and viewed the relationship as instrumental: useful for as long as it served Russian interests in dealing with the West.

The increase in the number of terrorist attacks initiated by rebels from the Caucasus in Russia also influenced the local elite’s attitude toward the Islamic Republic, as Iran began to seem more like an Islamic liability to Russia’s security. In many respects, this attitude is a product of the Russian historical perception of the Islamic world as a homogeneous unit. Many in the Russian ruling elite do not draw a distinction between the Shi’i and Sunni denominations, and accordingly see no difference between the Shi’i-Iranian state and Sunni-jihadist organizations operating in the Caucasus, despite the mutual animosity between them.

Concurrently, the Russian elite’s concerns about a nuclear Iran at its border also increased. The possibility that Iran would become a nuclear power in a region that is still under the dominant influence of Russia emerged as a potentially threatening scenario to Moscow’s interests in the former Soviet republics of Central Asia and the South Caucasus. In addition, trade relations with Iran were not as essential to Russia’s economy under President Putin as they were in Yeltsin’s era.

For its part, the Islamic Republic does not conceal its current suspicions of Moscow’s genuine motives toward Iran. Following Russia’s support for imposing further sanctions on Iran in the Security Council in June 2010, a conservative Iranian daily called on the regime to advance nuclear ties with Turkey, Brazil, and China at the expense of Russia, in order to demonstrate to Moscow that Iran’s nuclear program did not depend on Russia. The newspaper further added that Russia’s conduct toward Iran indicates that its leadership sees Iran as an “inferior partner”(Quds, 8 June 2010 in MEMRI report, 24 June 2010).

Presently, it seems that the “bargaining chip” approach governs Russia’s policy toward Iran. Although the Euro-Asian approach has virtually disappeared from the current political discourse of the Russian ruling elite, its legacy and influence on the history of bilateral relations between the two countries should not be underestimated.

Finally, the increasing involvement of the United States in the former Soviet republics, such as Georgia, in addition to its efforts to place missile defense batteries in Eastern Europe, continues to raise serious concerns in Moscow. Therefore, Iran’s role as a “bargaining chip” in the relations between Russia and the United States has spiked in recent years. Under Putin and Dmitry Medvedev (1999-2012) Russia’s Iran policy has depended on the concessions Washington is willing to make and the benefits for Moscow. Hence, at least for the time being, the Russian-Iranian relationship appears to be an episodic marriage of convenience intended to foil the U.S. rather than a serious strategic alliance■

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il, Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 52 ● 1 July 2012

© All rights reserved