Previous Reviews

Number 61 ● 23 October 2013

MOSADDIQ AND THE AUGUST 1953 COUP - SIXTY YEARS AFTER

Miriam Nissimov*

On August 19, 2013, Iran marked the 60th anniversary of the military coup and deposition of Mohammad Musaddiq, the Iranian prime minister who led the historic movement to nationalize the country's petroleum industry in the early 1950s. Over the years, the gripping political events that engulfed Iran in the early 1950s became the topic of dozens of books, biographies, and academic articles in and outside Iran. Even after 60 years, many questions concerning Musaddiq's leadership, his struggle to nationalize the oil industry, and the reasons for the US involvement in the efforts to topple him are still in dispute. The anniversary this summer triggered a new flurry of debates in leading newspapers and in special supplements published by the Islamic Republic’s online news agencies. Also this summer, the US National Security Archives made available online 17 recently declassified documents that expose various aspects of the CIA’s involvement in the coup d'état against Musaddiq.

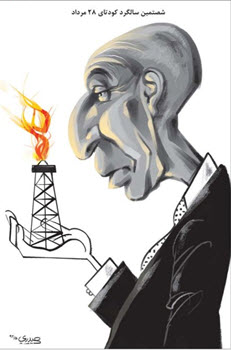

Sixty years to the coup of August 19th, cartoon by Hadi Heidari, retrieved from Sharq 29/07/13

Since the 1950s, Musaddiq and the National Front (Jebheh-yi melli), the political movement he headed, have symbolized Iran’s national struggle for independence and sovereignty. Founded as a coalition of political groups and parties in 1949, the National Front stood for secular nationalism. Despite its structural changes over the years, and the fact that its leaders included observant Muslims such as engineer Mehdi Bazargan and Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleqani, the National Front consistently operated in the name of Iranian nationalism. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, Musaddiq's political heritage and the events of August 1953 are typically discussed on the backdrop of the country’s efforts to emphasize the focal role of the Ulama in the national memory. Since its foundation, the Islamic Republic of Iran has sought to offer a historical reading that accentuates the significance of religious faith and motivation and the contribution of the Shi'i clergy in promoting historical changes in Iran, and especially their unique contribution to the consolidation and leadership of social movements.

In late 1978, while in Paris, Khomeini was asked to compare the struggle that he himself was leading to Musaddiq's movement. Khomeini replied that his movement was much deeper and that it was essentially a religious movement, while Musaddiq's struggle had been only political. Criticizing the efforts of Musaddiq and Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani, Musaddiq's political partner to nationalize the oil industry, Khomeini stated, “At the time, I wrote and told Kashani that he must address the religious aspects. But instead of giving priority to religious considerations over political considerations, he himself became a political figure when he was appointed chairman of the Majlis, which was a mistake. I said that one ought to act on behalf of the religion not on behalf of politics.” (Sahifeh-ye Nur, vol. 5). Khomeini's disapproval of Musaddiq and the National Front grew more intense in the first years after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, when public figures associated with the National Front and Musaddiq's worldview protested against the Islamization that Khomeini had instigated in Iran. In the early 1980s, on the backdrop of internal discord between the country’s political forces, Khomeini stated, “We have suffered enormously from nationalism (melliyat). I do not want to say that during the years of nationalism, during the time of that man [Musaddiq] who was frequently praised, what a slap in the face this man gave us” (ibid, vol. 13). Elsewhere Khomeini stated that the National Front was a null movement from its inception, which opposed Islam and the clergy. Using the allusive pronoun an rather than explicitly stating Musaddiq's name, Khomeini expounded on the insults that were hurled at the clerics during that period and added that Musaddiq was not a “Muslim” (ibid, vol. 14).

Thirty-four years after the foundation of the Islamic Republic, and on the 60th anniversary of the events of August 1953, the historiographic discourse concerning Musaddiq's era is still a contested topic in Iran. Historian Ali Bigdeli pointed to two main trends in the scholarly writings on the political events of the early 1950s. Some historians and authors, Bigdeli noted, are siding with Ayatollah Kashani and point an accusing finger at Musaddiq. This trend is led by individuals largely associated with religious organizations, and its narrative also featured in school textbooks. Other authors, in contrast, portray Musaddiq as a model of nationalism and the first person in the region to campaign for the independence of countries that were subject to “British exploitation.” Supporters of this view, added Bigdeli, believe that Mosaddiq was a source of inspiration for other leaders in the region in their struggle against Great Britain (IBNA, August 19, 2013).

Similar views are reflected in several interviews published last summer in newspapers and posted on news websites. In a series of interviews conducted by the website Tarikh-e Irani, several prominent intellectuals were asked to express their opinion on Musaddiq. Translator Abdallah Kausari noted that he considered Musaddiq a tragic hero, “on whose shoulders a heavy burden was placed, and who remained alone under this burden.” He stressed that “the difficulties that Musaddiq faced were not merely his; these were difficulties of an entire nation that suffered from disunity and a lack of political experience […]”. Responding to a question on Musaddiq's place in the historical memory of the Islamic Republic, Kausari stated that despite media efforts to show Musaddiq in a negative light, for many Iranians Musaddiq continues to symbolize the struggle for genuine independence, the rule of law, and democracy (Tarikh-e Irani, August 31, 2013).

Intellectual Ehasan Shariati, son of the Islamic Revolution ideologue Ali Shariati, compared Musaddiq to Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, and Martin Luther King, and argued that, like them, he was a man of ethics and morality. Shariati noted that Musaddiq's political actions should be judged for their long-term ethical and national effects, and not only from the narrow perspective of their immediate success. Musaddiq is the symbol of different kind of "Iranianess," Shariati stressed, adding that the world tended to equate Iran with monarchism, the supremacy of clergy, or the ancient class system, but people like Musaddiq represented a different kind of Iranianism, an Iran of culture, heroism, and nobility of the spirit (Tarikh-e Irani, August 28, 2013). Other intellectuals who were interviewed by the website also addressed Musaddiq as a symbol of democracy and aspirations for national freedom (Tarikh-e Irani, August 13, 18, 19, 24, 23, 2013).

Portrayals of Musaddiq as a national hero also found expression in an art exhibition held in a private gallery in Teheran marking the 60th anniversary of the August 1953 coup. The exhibition included portraits of Musaddiq and a documentary film entitled “In memory of a national leader” (yaadi az yek rahbar-e melli). In their introduction to the exhibition, the curators wrote that many efforts had been made in the last several decades to erase Musaddiq's name and image from the history of the nation, and that the exhibition was organized in honor of this extraordinary man, to demonstrate that “history is no longer written by the victors” (Iranboom website).

In contrast to these opinions, news sites associated with the conservative camp directed readers’ attention to Musaddiq's political errors. A review by the conservative news site Asre Emrooz stated that Musaddiq made his greatest mistake when he distanced himself from the religious forces. According to this review, Musaddiq erred in foreign policy by trusting the United States and failing to identify its true intentions. “The prime minister of Iran believed at the time that since the United States had no history of ‘negative’ involvement in Iran, it could be trusted; by doing so, he effectively prepared the ground for the US entry into Iran, and the background for the overthrow of his own government” (Asre Emrooz, August 19, 2013).

The conservative news site Javan published a series of interviews with first-hand witnesses to the events of August 1953, and it too presented a critical view of Musaddiq and his political legacy. Reminiscing about the period in question, the interviewees stressed Kashani’s focal role in the struggle, and castigated Musaddiq, whose political actions led to the schism between the national and the religious forces (Javan, August 17, 2013). Similar accusations were also expressed at a joint conference organized by the National Library and Archives organization of Iran (NLAI). In his speech at the conference, Archives Chairperson Dr. Eshaq Salehi discussed the focal role of the Ulama in the struggle led by Musaddiq, and stated that historical documents show that Kashani warned Musaddiq of the “imminent” possibility of a coup one day before it occurred, and he even offered his assistance, but Musaddiq placed his faith in the people’s support and rejected Kashani’s offer.

In summary, 60 years after the August 1953 coup, and more than three decades after the foundation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iran is occupied with the formation of its national memory of this historical event. Together with those who highlight Musaddiq's political errors and stress the contribution of the religious establishment to the struggle—especially Kashani—others continue to promote Musaddiq as a symbol of Iran’s struggle for independence, liberty, and democracy■

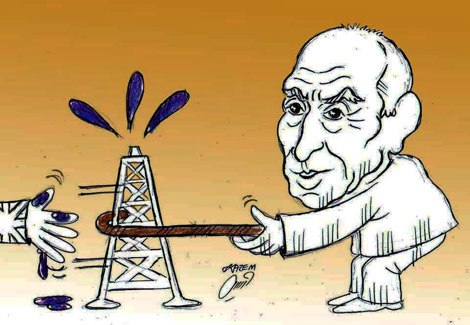

Sixty years to the nationalization of Iran's petroleum industry (March 1953).

Cartoon by Hosseim Kazem, retrieved from Bahar News, 21/03/13.

*Miriam Nissimov is a research fellow at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 61 ● 23 October 2013

© All rights reserved