DISILLUSIONED HOPE: IRAN AND MOHAMMAD MORSI'S GOVERNMENT

Number 58 ● 16 July 2013

DISILLUSIONED HOPE: IRAN AND MOHAMMAD MORSI'S GOVERNMENT

Raz Zimmt*

The victory of Mohammad Morsi in the Egyptian presidential elections in June 2012 was welcomed with explicit satisfaction in Iran. Tehran hurried to present the election of a candidate representing the Muslim Brotherhood as another expression of the Islamic Awakening in the Middle East, which draws its inspiration from the Islamic Revolution (see Iran Pulse no. 46). President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called Morsi the day after his election, congratulated him and expressed his hope for improved relations between the two countries (see Iran Pulse no. 29). The Foreign Ministry in Tehran issued an official announcement praising the Egyptian people on their determination to realize the lofty ideals of the Egyptian revolution and noted that Egypt was in the final stages of the Islamic Awakening (ISNA, June 24). Conservative media outlets reported extensively on Morsi's election, stressing his piety and his anti-Zionist and anti-western stances.

The response to Morsi's victory reflected Iran's sober assessment and acknowledgment of the constraints that the new president would face. A few days after Morsi's victory several Iranian media outlets expressed doubts that the new Egyptian government would be able to adopt a policy consistent with the expectations of the Islamic Republic. The Iranian press anticipated that the Egyptian army still had significant influence over the political system, and claimed that many supporters of the Islamic camp were members of the Salafi movement who hold extreme anti-Shi'ite positions. Doubts were also raised regarding the foreign policy that Morsi could be expected to choose. The reformist daily Sharq claimed that the attitude of many revolutionaries in Egypt towards developments in Syria was inconsistent with Iranian policy supporting President Assad (Sharq, 26 June 2012). The conservative website Tabnak opined that the election of Morsi would not necessarily lead to a significant improvement in the relationship between Egypt and Iran because Morsi would be forced to take into account political and economic considerations related to his country's relationship with Saudi Arabia and its peace agreement with Israel. Despite these doubts, Iran did not hide its hopes that the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood would start a new page in the relationship between the two countries, and provide Tehran a new opportunity to improve its connections with Cairo and reinforce its status in the region (Tabnak, 25 July 2012).

It quickly became clear that the political situation in Egypt was more complex than initially apparent, and the rise of Islamic forces did not foretell a strategic change in the relationship between Cairo and Tehran. Within a short time, the foreign policy adopted by Morsi vexed the Iranians. Egypt became one of the main supporters of the Syrian opposition, established a joint Sunni front with Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar against Iran, continued to maintain a close relationship with the US and honor its peace agreement with Israel. When President Morsi took his first international trip after election to Saudi Arabia in July 2012, the daily newspaper Jomhouri-ye Eslami accused him of being a traitor to the values of the Egyptian revolution and claimed that the Muslim Brotherhood had not taken any steps to meet the demands of the Egyptian revolution, first and foremost eliminating any remnants of the previous regime, canceling the Camp David agreements and severing Egypt's dependence on the West and its allies in the region (Jomhouri-ye Eslami, 15 July 2012).

Only a few months after Morsi's election, Iranian doubts about the possibility of a change in Egyptian policy had turned into major disappointment, which led to intensified criticism. Egypt's moderate response to the Israeli "Pillar of Defense" operation in the Gaza Strip in November 2012 met with an aggressive response from Iran. Tehran, watching with concern as Hamas moved closer to Egypt at the expense of its relationship with Iran and as the events in Syria had a destabilizing influence on solidarity of the "axis of resistance" it had formed with Hezbollah and Hamas, used the Israeli operation as an opportunity to attack Egypt's regional policy. The conservative newspaper Javan censured Morsi and his government, and called on young Egyptians to demand that their new government return to the revolutionary track and realize Egypt's commitment to the Palestinians. The paper claimed that citizens of Egypt expected their government to sever its ties with Israel, cancel the peace agreements, and open a channel for helping the Palestinians (Javan, 17 November 2012).

In January 2013, a conference supporting the Arab minority in Khuzestan province convened in Cairo. Participants included representatives of the Arab separatist movement active in southwestern Iran, Muslim clerics, representatives of Al-Azhar University in Cairo and representatives of political parties identified with Islamic movements, led by President Morsi's advisor 'Imad Abdel Ghafour who expressed support for the struggle of the Arab minority in Iran. Iranian media strongly criticized Morsi personally and his government for allowing the conference to convene. The website Tabnak called Morsi a "second Mubarak" who takes orders from his masters in London and Washington, and called on the Iranian government to demand a formal apology from Egypt (Tabnak, 11 January 2013).

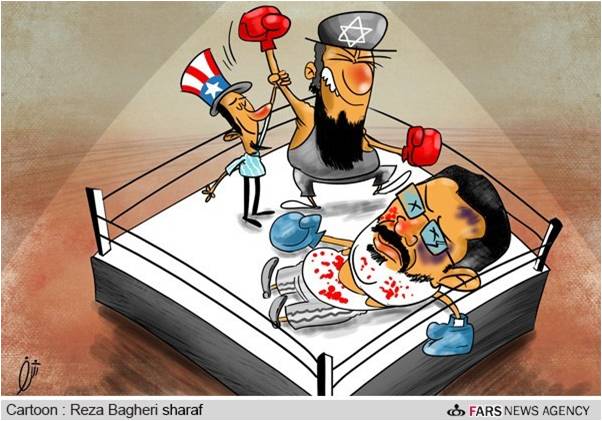

Criticism of Morsi's policy continued until his last days in office. The killing of four Shi'ites, including an Egyptian Shi'ite leader, in the village of Zawiyat Abu-Musallam in the Giza region on 23 June 2013, brought a furious response from Iran. Although Iranian Foreign Ministry was content to issue a relatively moderate statement of condemnation, senior religious leaders and media outlets charged Morsi and his government with responsibility for the attack. Jomhouri-ye Eslami accused the Egyptian president of allowing the US and Israel to retain the status they had in Egypt during the presidencies of Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak. In an editorial published on June 26, the paper claimed that the Egyptian government led by the Muslim Brotherhood was continuing to maintain a close relationship with the US and Israel, severing its ties with Syria in order to protect the "terrorists" fighting against Assad's regime, acting in coordination with the regional policy of US and Israel, cooperating with reactionary Arab leaders against the Islamic Awakening in the Arab world, assisting radical Salafi groups, and limiting the religious freedom of Egyptian citizens.

The editor of Kahyan, Hossein Shariatmadari, also attacked the Egyptian government in an editorial entitled "Remember that You Are Indebted [to Us]!" He claimed that Egypt owes its liberation from the US and Zionists to Iran and if it were not for the commitment, sacrifice and patience of the Shi'ites in Iran, Egypt would still be under Mubarak's rule. The paper severely criticize President Morsi for his participation, two weeks previously, in a conference supporting Syrian opposition that was held in Cairo with the participation of Salafi groups and other radical Islamic organizations. Shariatmadari contended that his participation in the conference and decision to cut his country's ties with Syria effectively meant that Morsi was in a coalition with the Salafis. Although the government of Egypt and the Muslim Brotherhood did not play a direct role in the attack against the Shi'ites and even condemned them, their ill-considered positions and actions, encouraged Salafis to commit these crimes (Kayhan, 26 June 2013).

Considering the disappointment with the policy adopted by Morsi's government and lost hope of a significant improvement in relations between the two countries, it is not surprising that the military coup and Morsi's ouster from the presidency were received in Tehran with a great deal of satisfaction. Although Iran officially condemned the military intervention in politics, and stressed that it would not interfere in Egypt's internal political crisis, it placed most of the blame for the situation on the failures of Morsi's government. An official statement issued by the Foreign Ministry said that Iran follows with concern the deterioration of the internal situation in Egypt, which could be utilized by Israel and the West to divert Egypt from the path of the revolution. In an interview with the news agency ISNA (7 July 2013), Chairman of the Majlis National Security and Foreign Policy Committee, Alaa al-Din Boroujerdi, said that Iran is ready to assist in bringing peace to Egypt to ensure its national interests. He noted, however, that the events in Egypt are the result of erroneous behavior by the Muslim Brotherhood that did not eradicate the influence of the remnants left from the old regime and gave them a chance to regain power. Boroujerdi also attributed responsibility for the Morsi government's downfall to both their failure to improve the Egyptian economy and the foreign policy it adopted.

Iranian media also condemned the Egyptian military coup against a democratically elected government but stressed that Morsi's policy had made a decisive contribution to his downfall less than a year after being elected. The media contended that the refusal of the Muslim Brotherhood to renounce ties with Western countries and their allies in the region and Morsi's failure to keep the promises given to the Egyptian people led to the eventual loss of popular support for his rule.

Even the Friday prayer leader of Tehran, Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami, accused Morsi of being responsible for his own downfall, claiming that the Egyptian president was unable to distinguish between friends and foes, and that his policy cleared the way for the military coup. He accused the Egyptian government of assisting radical Salafi elements instead of working for Islamic unity, leading a campaign against Iranian and Shi'ites, and continuing ties with Israel contrary to pre-election promises. He also criticized the failed domestic policy of the Muslim Brotherhood that did not meet the demands of Egyptian citizens (Mehr Agency, 5 July 2013).

The fall of the Egyptian government does provide Iran with a short-term chance to realize some goals of its regional foreign policy. Developments in Egypt may divert regional and global attention from the continuing civil war in Syria to the deepening political crisis in Egypt. Morsi's ouster denies the Syrian opposition one of its main supporters, and may weaken the Islamic-Sunni front that posed a significant challenge to Iran in the last two years. The fall of the government led by the Muslim Brotherhood also threatens to deny Hamas one of its most significant allies and force it back into the arms of Iran, from whom it distanced itself due to disagreements concerning the crisis in Syria.

Despite its disappointment with Morsi, even after the military coup in Egypt Tehran continues to claim that the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood does not reflect the end of the Islamic Awakening. For example, Ayatollah Ahmad Khatami stressed in his weekly sermon that Morsi's fall does not herald the collapse of the Islamic Awakening and that Egyptian citizens are defending that awakening. However, it is doubtful that the fall of Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood will significantly alter the regional balance of power in favor of Iran. The fact that the Egyptian army has taken power indicates that the developments in the Arab world are not evidence of an Iranian-inspired Islamic Awakening. The great distrust of Iran prevalent in Sunni Arab countries is not likely to pass from the world and the Syrian crisis will continue to present a significant challenge to Iran and its Lebanese ally Hezbollah in the coming months. Saudi Arabia's rapid aid to Egypt, which is in dire economic straits, seems to ensure that Egypt will remain in the anti-Iranian camp. A few days ago the Egyptian Foreign Ministry spokesman, Bader Abdel-'Ati, made a statement accusing Iran of interfering in the internal affairs of Egypt (Fars News Agency, 8 July 2013). This may indicate that the window of opportunity for improving the relationship between the two countries, which opened with Morsi's rise to power, has closed again.

The military coup in Egypt may actually have a positive impact on Iran in domestic contexts. The spread of violence in Egypt alongside the bloody civil war in Syria continually demonstrate to Iranians that a revolutionary, violent overthrow of the regime is not a magic solution that guarantees a solution to their problems. The bloody events in the Arab world could strengthen the consciousness among the people of Iran, who recently elected a new president, that political stability might be preferable over striving for political freedom through a revolution, the results of which are not known in advance. In the sea of regional turmoil, Iran actually appears to have become an island of stability■

*Raz Zimmt (PhD) is a research fellow at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies and editor of the publication Spotlight on Iran published by the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 58 ● 16 July 2013

© All rights reserved