IRAN GOES TO THE POLLS: NEW PRESIDENT, OLD REALITY

Number 57 ● 5 June 2013

IRAN GOES TO THE POLLS: NEW PRESIDENT, OLD REALITY

by Raz Zimmt*

On June 14, 2013, Iranian citizens will go to the polls to elect a president for the eleventh time since the Islamic revolution in 1979. In the Islamic Republic, the supreme leader serves as head of state and manages most of the country’s affairs, particularly its foreign policy. His powers were extended even further when the constitution was amended after Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini’s demise and power was transferred to his successor, Ali Khamene’i, in 1989. However, in his capacity as head of the executive branch, the president of Iran does have significant influence over the management of state affairs, especially the economy and domestic policy.

Four years have passed since 2009 when riots followed claims by the reformist opposition that the previous presidential elections were rigged. More than 50 million Iranians are eligible to vote and elect a new president to replace Mahmoud Ahmadinejad who is completing two consecutive four-year terms, the maximum permitted by the constitution. Ahmadinejad, who surprised many people in Iran and political analysts when he won the 2005 election with a victory over former Iranian president Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, finishes his second term politically isolated after two years of unprecedented power struggles. Since his first election, Ahmadinejad has enjoyed the public support of Khamene’i, yet his policies in recent years have been controversial and aroused stern indignation of the conservative religious establishment, led by the supreme spiritual leader. The conservative establishment has even associated the incumbent president with the “deviant faction” (jaryan-e enherafi), a derogatory term often used to refer to his supporters, especially his former bureau chief, Esfandiar Rahim Masha’i.

The tension between Ahmadinejad and Khamene’i became explicit in April 2011 when the leader refused to approve the dismissal of Intelligence Minister Heydar Moslehi, a move which was rapidly transformed into a bitter political crisis within Iran’s leadership. The dispute between supporters of Ahmadinejad and Khamenei’s loyalists is more than a political power struggle; it reveals a sharp ideological rift. The messianic inclinations of the president’s political allies and their emphasis on the national-cultural component of Iran’s identity rather than Islam, combined with the challenges they posed to the status of the clergy, were perceived by many in the conservative circle of the ruling establishment as a major threat. Consequently, the conservatives diverted most of the efforts previously directed at curtailing the reformists’ campaign, against the president and his political supporters.

|

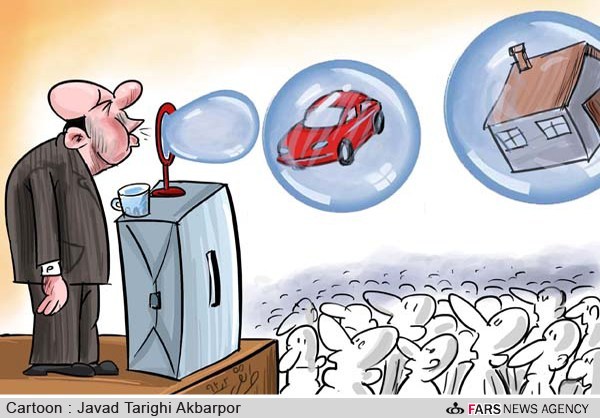

On the eve of the election, Iran’s ruling elite is confronted not only with political rifts but also with a severe economic crisis, exacerbated by the economic sanctions imposed by the West in response Iran’s nuclear development program. Recriminations are running rampant between the government and its political opponents. Whereas the president and government contend that the international sanctions are the main cause of the economic crisis, their opponents argue the crisis mainly stems from the populist and irresponsible economic policies of the government during the past eight years. The economic crisis, inflationary surge, high unemployment rates (especially among Iran’s youth) and the collapse of the local currency (Rial) increase the regime’s fear that public protests will resume and undermine domestic stability.

A total of 686 candidates (including 30 women) submitted their candidacy for the upcoming presidential election. On May 21, the Interior Ministry published the names of eight candidates approved by the Guardian Council. During their deliberations, the Council decided to reject the two leading candidates: Rahim Masha’i and Hashemi Rafsanjani, currently chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council. The latter submitted his candidacy on the last day of registration, surprising many in the Iranian political system who had speculated that he would not run again.

The disqualification of two leading candidates might attest to the regime’s fear that Rafsanjani could undermine the authority of Khamene’i, as well as to its dislike of Masha’i who enjoyed the support of Ahmadinejad and his allies. Soon after disqualifications were announced, claims were heard that supporters of the “incitement stream” (jaryan-e fetneh, meaning the reformist opposition that supports Rafsanjani) and supporters of the “deviant faction” led by Masha’i were conspiring to destabilize the regime. After Rafsanjani declared his candidacy, political opponents waged a personal campaign against him, accusing him of collaboration with the leaders of the 2009 riots, extravagant living and corruption. Moreover, they claimed that his age, 79, made him unfit to serve as president.

The eight approved candidates for the presidency are mostly affiliated with the mainstream Iranian right. Three candidates, representing the “coalition of progress” (e’telaf-e pishraft, also known as “coalition of 2+1”) are identified with the traditional conservative camp: Ali Akbar Velayati, Khamene’i’s advisor for international affairs; Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, mayor of Tehran; and Gholam-Ali Haddad Adel, former Majlis speaker. Qalibaf (b. 1961, Mashhad) has held numerous senior positions, including chief of internal security forces and commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ Air Force, and is considered one of the most promising candidates. He is especially popular in Iran for his accomplishments as mayor of Tehran since 2005. His image as a pragmatic technocrat and moderate positions may help him garner public support, while simultaneously provoking criticism from right-wing conservatives and, possibly, from the supreme leader. Moreover, his involvement in the suppression of the student riots in 1999 and in 2003 could pose an obstacle to his efforts to mobilize support among young voters and supporters of the reformist camp. Velayati (b. 1945, Tehran) is considered a close confidant of the supreme leader, but seems to lack public sympathy.

The secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, Saeed Jalili (b. 1965, Mashhad) is also considered to be one of the prominent candidates in the upcoming elections. Representing the Steadfast Front (jabhe-ye paidari), Jalili is associated with the radical right wing of the conservative camp, and is known for his extreme positions and political loyalty. Similar to Velayati, he is considered a trusted confident of Khamene’i. However, his lack of experience, especially in economic administration, might hamper his chances of receiving sufficient political and public support to win the elections.

Two of the approved candidates could potentially win the support of reformist voters. Hassan Rouhani (b. 1948, Semnan Province) has held numerous senior political and security-related positions since the revolution, and served as the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council between 1989 and 2005. Rouhani still functions as Khamene’i’s personal representative to the Council, but his close relationship with Rafsanjani, moderate positions on domestic affairs and the pragmatic line he advocates concerning Iran’s foreign and nuclear policies in his capacity as chief nuclear negotiator with the West, have been criticized by the conservative camp. Despite any reservations Khamene’i may have, Rouhani might be supported by reformists and pragmatic conservatives. Mohammad Reza Aref (born in 1951, Yazd), who served as deputy of former president Mohammad Khatami (2001-2005), is considered a moderate reformer, and might win the reformists’ support. However, it is also possible that he will decide to avoid splitting the reformist camp and withdraw his candidacy just before the elections, in favor of Rouhani whose chances of being elected are considered better.

Two other candidates in the elections are less likely to garner significant public support: Mohsen Rezae’i (b. 1954, Khuzistan), secretary of the Expediency Discernment Council and former commander of the Revolutionary Guards, and Mohammad Gharazi (b. 1941, Isfahan), who served as the Minister of Oil in the government of Mir-Hossein Mousavi (1981-1985) and Minister of the Post in Rafsanjani’s government (1985-1997).

The list of approved candidates for the presidency reflects the narrowing scope of the ruling political elite in Iran. In recent years, the regime has gradually pushed some major political forces out of the political consensus. The struggle between the regime and the reformist opposition, which culminated in riots of 2009, led to marginalizing leaders of the reformist camp. In the past two years, the regime directed most of its efforts against President Ahmadinejad and his associates, climaxing with rejection of his preferred candidate. Rafsanjani was not only disqualified as presidential candidate, he was removed from giving the Friday sermon in Tehran and dismissed as chairman of the Assembly of Experts, which completed the process of ostracizing any competing political or ideological currents. This process may undermine the legitimacy of the regime, which once purported to combine Islamic notions of divine sovereignty with democratic-Republican notions of the sovereignty of the people.

The exclusion of reformists from the political system also has significant social- economic implications. The educated, urban middle-class has increased significantly in recent decades, and forms an important support base for the reformist camp. Educated and urban young people formed the hard core of the “Green Movement” that led the 2009 protest. Pushing reformists out of popular, elected political institutions might leave the new middle class without proper representation. Among the prominent candidates in the current election campaign, Jalili is considered the socio-economic successor of Ahmadinejad’s policy, and he is directing his efforts towards mobilizing support among the lower classes and in the periphery. On the other hand, Velayati and Rohani identify mainly with the old political elite and the traditional middle class, relying on their constituencies among the clerical establishment and the bazaar merchants. Following the 2009 elections, many Iranians feel completely deprived of any ability to influence the political system, although their influence was quite limited in the first place. The concurrence of a relatively homogenous list of candidates and the regime’s blatant “election modifications” (through the screening of candidates) might increase the level of despair and, under certain conditions, lead to renewed political protests.

The list of approved candidates also embodies another significant process the Iranian political system has experienced in recent years: the gradual erosion of the clergy’s status and a decrease in their representation in elected bodies. At the same time, the political influence of technocrats, mostly from the Revolutionary Guards, on the political elite has increased. Of the eight candidates, only Rouhani had religious training in addition to his western education, and holds a religious title (Hojjat-ol-Islam). Seven candidates have doctoral degrees: Qalibaf in political geography, Velayati in medicine, Haddad Adel in philosophy, Jalili in political science, Rouhani in law, Rezaei in economics and Aref in electrical engineering. Both Rezaei and Qalibaf held senior positions in the Revolutionary Guards, and Jalili joined the Basij during the Iran-Iraq War, during which he lost a leg.

In conclusion, unless something unexpected happens regarding one of the two candidates identified with the moderate wing of the reformist camp (Rouhani or Aref), it seems likely that one of the three prominent conservative candidates (Qalibaf, Velayati or Jalili) will win the election. The election of a candidate identified with the line led by the Supreme Leader Khamene’i will enable the regime to continue following its current strategy for both foreign and domestic policies. The election of a conservative president who is politically loyal to the leader might indeed allow Khamene’i to maintain his position in the near future by relying on his supporters in the political system and the Revolutionary Guards, but it will not necessarily help him solve Iran’s economic crisis. In the medium and long ranges, however, it might also exacerbate the crisis over the regime’s legitimacy, because the pressures of recent years have forced it to abandon any semblance of political democracy. The erosion of legitimacy and intensified socio-economic troubles call into question the ability of the clerical regime to successfully cope with the challenges that lie ahead in Iran’s future■

*Raz Zimmt (PhD) is a research fellow at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies and editor of the publication Spotlight on Iran published by the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 57 ● 5 June 2013

© All rights reserved