Previous Reviews

Number 70 ● June 15, 2014

Number 70 ● June 15, 2014

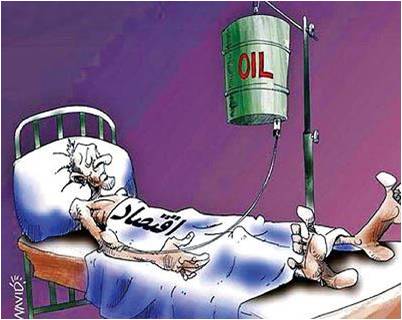

IRAN'S ECONOMY ON THE VERGE OF COLLAPSE?

by Paul Rivlin*

Following the implementation of a subsidy reform program in late 2010 and the tightening of international sanctions in 2012, Iran's economic performance declined sharply. To what extent did these mounting economic pressures move Iran to sign the November 2013 interim agreement with the P5+1 concerning its nuclear program? New evidence suggests that by the spring of 2013, concerns of an imminent economic collapse may have been a key factor in the Iranian leadership’s decision to open negotiations on its nuclear program.

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Emrooz va-farda, November 3, 2013 |

In April 2013, a letter sent by the Governor of the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) to Mohammad Reza Rahimi, first Vice President and head of the Economic Special Measures Committee was leaked. In it, the Governor explained that the financial system was on verge of bankruptcy and that the CBI could lose control of the banking system. Other letters discussing potential governmental responses were also leaked. These documents, assuming that they are authentic, are important because they indicate what was happening in the Iranian economy in early 2013, and they reveal a discrepancy between official statistics and reality. The latter can be grasped by comparing data revealed in the letters with the statistics featured in CBI publications available on its website. The depth of the crisis revealed in the governor's letter also suggests why Iran agreed to begin negotiations on its nuclear program.

As a result of the deterioration of the financial state of Iran’s banking sector, the CBI had been compelled to provide 500 trillion rials ($40 billion) in assistance to the banks. Real interest rates (after allowing for inflation) were negative and the banks had granted loans that were not matched by their deposits. As a result, they had insufficient capital (their own funds) and so depositors were in effect becoming reliant on assistance from the CBI (although its ability to do so was compromised by the economic slowdown). Debts to the banks exceeded 750 trillion rials ($60 billion), and many borrowers had difficulty repaying their debts. As a result, the banks initiated legal proceedings against 7.2 million of their 34 million debtors. The slowdown in the economy further destabilized the financial system.

Sanctions triggered a 50 percent drop in oil sales, which led to a shortage of foreign currency and also limited Iran’s access to much of its foreign reserves. A large share of the gold reserves had been sold to the public, while other foreign reserves had been allocated to the National Development Fund and other projects, and so were not available to, or did not belong to the CBI. Had the crisis deepened and threatened a further devaluation of the rial, the country would have faced serious challenges acquiring the foreign currency required to pay for its imports. This would have resulted in shortages of many basic, imported commodities, including paper for printing the banknotes that were needed at an increasing rate because of rapid inflation that reached 85 percent in 2012-2013.

Much of the economy’s productive sector was also on the verge of collapse as a result of sanctions that caused rising prices of imported raw materials, and a consequent drop in domestic demand. Production in the automobile industry, for example, fell by 47 percent. Automobiles, aviation and other industrial sectors anticipated massive layoffs because they could not pay their wage bill and were likely to reach the brink of collapse in 2013-2014.Due to the fall in government revenues from oil sales, taxation, and privatization, a huge budgetary deficit was forecast for 2013-2014.

The CBI publishes annual and quarterly economic reports. At the time of writing, the most recent annual report on the bank's website was for the year to March 2012 and the most recent quarterly report was for the year ended in March 2013. Additional recent economic indices were also published: the consumer price index for November 2013 reflected an annual rate of inflation of 31.9 percent, with food prices rising 38.7 percent. These figures were much lower than the statistics cited in the Governor's letter.

According to CBI, Iran's population is growing by 1.2 percent, which meant that in 2012-2013 (March 21, 2012 – March 20, 2013), the absolute increase was just over 900,000. Unemployment reached 12.2 percent, but was 24.5 percent among 15-24 year olds. Unemployment in the first half of 2012-2013 for the population over age 15 was 25.4 percent, but 38.8 percent for the population between the ages of 15 and 29. The Central Bank's definition of unemployment was someone who worked less than two days a week (the international standard), whereas the Central Bureau of Statistics’ (CBS) definition was someone who worked less than two hours a week. This means that CBS figures are misleadingly low. In 2012-2013, GDP declined by 5.8 percent and as a result, GDP per capita fell by 6.9 percent. Oil export revenues declined from $118.3 billion in 2011-2012 to $68.1 billion in 2012-2013, a decline of 42.4 percent.

Underlying these developments were three major economic problems. The first is the legacy of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad whose government wildly over-spent. Ahmadinejad's administration was, among other things, responsible for an enormous increase in liquidity (monetary expansion). The government's operating budget rose from 127 trillion rials in 2009-10 to 321 trillion rials in 2012-13,largely financed by borrowing and printing money. Indebtedness of the public sector (including the Central Bank) to the banking system increased from 364 trillion rials in 2009-10 to 910 trillion rials in 2012-13. The Central Bank was forced to borrow from the private sector and allocate funds to new projects in order to create two million jobs, complete the Mehr project designed to provide low-cost housing in the periphery of large cities, and provide cash-payments designed to replace subsidies. All three projects failed and the increase in liquidity accelerated inflation.

To fight inflation, Ahmadinejad opened the economy to cheap imports, especially from China, which competed with local production. Of the nearly $700 billion in oil-export revenues received during his term, $440 billion were spent on imports. Foreign currency received from exports of a depleting resource was thus increasingly used to import consumer goods, resulting in the devastation of domestic industries.

In December 2010, the Ahmadinejad government introduced a radical reform of the subsidy system and an end to the sale of government-supplied energy, water, power, and other items to the public for as little as 25% of their international prices. The Subsidies Targeting Act called for the gradual raising of prices to international levels over five years.The budgetary cost of the previous subsidy program was more than $25 billion annually, and close to $100 billion in opportunity costs to the economy. Some 50% of the savings to the treasury were to be paid back to consumers to compensate for their higher expenditures; 30% was designated to incentivize energy-intensive industries, and partially compensate for their higher cost outlays; and the remaining 20% was to be retained by the treasury to cover administrative costs.

Instead of subsidies, cash payments were made to the public, but programs went awry from the outset. The potential number of welfare recipients, the scale of cash payments to each individual, and the scope for fraud were all grossly underestimated.

The program became a virtual universal handout instead of being limited to welfare for the poor. Similarly, although monthly cash payments to individuals were small (455,000 rials, equal to a mere 9 percent of the legal minimum monthly wage), the total volume of cash outlays was not accurately assessed. Hassan Rohani’s government also found that the number of individuals who were reportedly receiving these welfare payments was greater than the country’s total population. Afghan refugees, Iranians living abroad, and owners of forged identity cards have received a total of 56 trillion rials over the last three years. Revenues covered only 50 percent of the monthly obligations that currently amount to 35 trillion rials. The result has been deficit of $6 billion a year since the reform was initiated.

Potential revenues from higher food and fuel prices were also underestimated. The government assumed that higher energy and food prices would have little effect on consumer demand, yet simultaneously also assumed that higher prices would reduce waste and profligacy.

As expenditures rose and revenues proved inadequate, the deficit grew and was financed by borrowing from the CBI in the hope debts would be repaid from subsequent higher receipts. Failing to receive the anticipated revenues, the share of program revenues that was to have gone to the government (20%) was eliminated, and the industry’s share was drastically cut from the intended 30%. Faced with continued revenue shortfalls, the programs directed all the revenues to consumers in its second and third years.

The second problem was sanctions, especially those imposed by the US. The sanctions resulted in a sharp drop in oil revenues, from over $100 billion in 2011 to about $35 billion in 2012. Not only did oil revenues fall, but Iran's access to its foreign currency earnings in banks abroad was severely restricted and between $60 billion and $80 billion of the country's estimated $100 billion reserves were blocked. As a result, GDP fell in 2012 and in 2013. The sanctions also weakened the exchange rate of the Iranian currency. The official exchange rate of the rial against the dollar fell from 13,000 in September 2011 to 28,000 a year later while the unofficial rate fell to 37,000 in May 2013 (recovering to 28,000 following the interim nuclear agreement).Sanctions also contributed to the acceleration of inflation.

The third major problem was structural: much of the economy was run by powerful, but unaccountable groups such as the Revolutionary Guards and Bonyads (Trust Funds), which paid no taxes. While some of the Bonyads existed before the revolution, the Guards were its creation. Former president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani encouraged them to play a role in the economy following the Iran-Iraq war in order to reduce the burden on the state budget, and former president Ahmadinejad, a former Revolutionary Guard himself, expanded their role greatly by transferring privatized assets to them.

President Rohani, who was elected in June 2013, recognized the need to cut benefits while maintaining public support. This will be an extremely difficult task given that the population expects economic improvements following the interim nuclear agreement.

What are the immediate prospects for the Iranian economy? In two February 2014 two reports on Iran, the IMF stated that large external shocks and poor economic management over the past several years have had a significant impact on macroeconomic stability and grow and exposed the structural weaknesses in the economy as well as its policy framework. Specifically, a series of shocks, associated with the implementation of the first phase of the subsidy reform, ambitious but inadequately funded social programs, and a marked deterioration in the external environment due to heightened trade and financial sanctions, have crippled the economy. Inflation and unemployment are high, while the corporate and banking sectors show signs of weakness. The economy continued to shrink in the first half of 2013/14, and IMF expected the GDP to decline by 1.75 percent in 2013/14. Annual inflation rate decelerated rapidly, from about 45 percent in July 2013 to less than 30 percent in December 2013. This drop reflects tighter CBI credit, the appreciation of the rial, and global disinflation in some key staples. Inflation could end at 20-25 percent by end-2013/14.

Prospects for 2014/15 have improved after the interim nuclear agreement but still remain highly uncertain. Under the current external environment, the IMF projects that the level of economic activity will begin to stabilize in 2014/15, with real GDP growing by 1.5 percent in 2014/15 and by 2.3 percent between 2015/16 and 2019/20. Inflation is expected to decline to 15-20 percent, excluding the impact of planned higher domestic energy prices.

Unemployment remains a major problem, especially among the young. In 2013/14, the overall unemployment level was estimated at 10.3 percent while that among the young was 24.3 percent. Labor force participation rate, which has fallen steady in the last 20 years, was only 36.7 percent and Under current conditions, unemployment is expected to double and reach 20 percent by 2018. Non-oil GDP would need to grow by six percent a year to reduce unemployment. This compares with zero average growth of non-oil GDP in 2011/12-2012/13, estimated negative growth of 1.4 percent in 2013/14 and forecast growth of two percent in 2014/15-2015/16.

This forecast implicitly relies on several crucial assumptions: Iran will conclude a final agreement on the nuclear issue, and will implement economic reforms of the kind favored by the IMF. Even in this optimistic scenario, the short- and intermediate-term economic prospects look tough. In a more pessimistic scenario, they look even worse■

* Dr. Paul Rivlin is a Senior Fellow of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle East and African Studies, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 70 ● June 15, 2014

© All rights reserved