Previous Reviews

Number 69 ● May 23, 2014

THE DEBATE ON TEACHING ETHNIC LANGUAGES IN IRAN:

CHANGE ON THE HORIZON?

Raz Zimmt*

A recurrent topic in Iran's contemporary public discourse concerns the government’s intention to implement Article 15 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic, which recognizes the right of minorities to study their native language in school. This article, which has not been implemented since the Islamic Revolution, allows the use of local and tribal languages alongside Farsi, the official language of Iran, in the press, media and in teaching literature in schools.

In January 2014, Hojatoleslam Ali Younesi, advisor to President Rouhani for ethnic and religious minorities, stated that the issue of minority language instruction is on the government’s agenda and that the Ministry of Education had begun formulating plans for its implementation (Mehr). Islamic Guidance Minister, Ali Jannati, also expressed support for this change and emphasized the government’s commitment to implementing Article 15 of the Constitution (Asr-i Iran). The officials’ statements followed Rouhani’s campaign promise to promote the rights of ethnic-linguistic minorities, including the right to teach their language in the educational system (ISNA). Ethnic minorities constitute nearly half of Iran’s population. They reside mainly near Iran's borderline areas: the Azeri Turks in the northwest, Kurds in the west, Balochis in the southeast, Turkmens in northeast and Arabs in Khuzestan to the southwest. The election of President Rouhani raised expectations among some minority groups that discriminating policy against them would change, especially considering that he won more than 70% of the vote in Balochi and Kurdish provinces.

Fear of the weakening of Farsi

The possibility that Article 15 of the Constitution might be implemented in the near future stirred a lively debate between proponents of teaching local languages in schools and their opponents, including members of the Academy of Persian Language (Farhangestan), which was established in 1935 to promote Farsi language and literature, and cleanse it from foreign influences. At a meeting with the Minister of Education, Ali Asghar Fani, most members of the Academy expressed strong opposition to permitting the study of local languages, defining it as a threat to the status of Farsi. Mohammad Ali Movahed, a member of the Academy, said that the government must not intervene in the issue of learning local languages and expressed regret that the government wishes "Farsi to be forgotten.” Another academy member, Fathollah Mojtabaei, was particularly critical arguing that teaching local languages is a “conspiracy” imported into Iran by Western countries who wish to divide the country. He warned that using local languages for education and science would cause Iran to lose ground. Majlis member Gholam-Ali Haddad Adel, president of the Academy of the Persian language, also expressed his reservation and warned against potential damages to Iran’s national assets, including Farsi, for the sake of temporary political gains (Fararu ).

One of the major concerns raised by opponents of the government’s initiative relates to the possible impact of teaching local languages on Iran's national unity. A scholar of Farsi language and literature, Hassan Anvari, told ISNA that implementation of Article 15 would harm the unity of the Iranian nation because Farsi serves as means for bringing together different groups in the country. He noted that there is a significant difference between teaching local languages in schools and teaching Arabic or English, because Arabic is the language of Islam and English is the language of science. Therefore, teaching them is not a problem (ISNA).

Another concern raised by critics of the proposal is a fear of strengthening separatist tendencies among ethnic minorities. The writer and translator, Mohammad Baghaei Makan, argued that even though no one objects to using native languages in principle, the teaching of local languages requires careful examination because it might be the beginning of a dangerous process. He noted that no one should ignore the fact that Iran faces separatist attacks from both [world] powers and groups with extremist tendencies, and that ethnic separatism has increased since the Islamic revolution because of the “weakness of cultural management” by the state (ISNA).

A campaign promoting the right to learn ethnic languages

In response to the criticism of the government’s initiative, its supporters commenced a public and media campaign designed to promote the teaching of local languages in the educational system, led by representatives of the ethnic-linguistic minorities and the reformist press. Jalal Jalalizadeh, a former Majlis member from Sanandaj, the capital of Kurdistan Province, called on the government to keep its promises with regard to teaching ethnic languages. He claimed that the “security approach,” which considers teaching the native languages a “plot” designed to divide Iran, has been preventing implementation of Article 15 for many years. Jalalizadeh rejected the argument that teaching local languages will encourage separatism among ethnic minorities, calling it “baseless.” Those who support teaching these languages are not advocating a split in Iran but implementing minority rights under the Iranian flag while maintaining territorial cohesion. Although a small minority disagrees, they represent only themselves. He further claimed that most members of the minority communities wish to realize their demands within the framework of the geographical boundaries of Iran (Fararu).

Former Majlis member from Tabriz, Akbar Alami, who is of Azeri origin and a proponent of the government’s initiative, explained in an interview with the reformist newspaper Etemad, that Iran is a puzzle of races and groups with unique languages, cultures, literature and folklore which contribute to its beauty. Attempts to force the use of Farsi while suppressing other languages, as was done in the Pahlavi period, will only increase the resistance and hostility of ethnic minorities towards the country’s official language. The state’s granting of full rights to ethnic groups and increasing their sense of dignity will strengthen their connection to the state and weaken separatist tendencies. He forcibly rejected the argument that teaching local languagesis is an expression of western conspiracy, calling it a false claim that stems from the misconception that national unity requires linguistic uniformity. Iran has always been ethnically and linguistically diverse, and it were the minorities who have usually protected its borders and territorial integrity (Etemad).

Articles published in the reformist press also expressed their opinion in favor of teaching local languages in schools. In an article titled “Teaching the native language: a right or a conspiracy?” published by the daily Shargh, journalist Asghar Zare' Kahnamouei criticized the position of members of the Persian Language Academy, calling it “regretful and surprising.” Teaching native languages, he further maintains, is a civil right that should not to be ignored, and it is enshrined in the Iranian constitution and various international conventions. Teaching local languages in schools does not pose any threat to national security and may even contribute to it because it will strengthen the minorities’ loyalty to the state and decrease separatist demands. In his view, the teaching of local languages is not expected to adversely affect the status of Farsi any more than teaching English or Arabic does. The defense of Farsi should not, he continues, come at the expense of other languages or at the price of denying the rights of ethnic groups (Shargh).

In an article published by Bahar News, Vahid Sadeghi, a scholar of Farsi language and literature, also expressed support for the teaching of local languages by indicating that Iran’s national unity is not based only on Farsi, but rather on other strong elements, such as: Islam, the mutual history of its residents, national valuesand common historical pride based on the Islamic revolution, the Iran-Iraq war, and tens of thousands of martyrs from among the ethnic and religious minorities who died for the revolution and their homeland. Teaching local languages will not weaken national unity, but rather preserve it. Sadeghi notes that Farsi continued to grow and expand, even when Arabic dominated Iran. The teaching of local languages will not come at the expense of learning Farsi, but will rather be an additional subject in schools, similar to English and Arabic. He also rejected the argument that teaching ethnic languages requires heavy financial investment. It can, he said, be based on teachers already working in the system and the publication of a few textbooks for additional languages is a trivial matter for the Ministry of Education, which publishes more than a thousand textbooks every year (Bahar News).

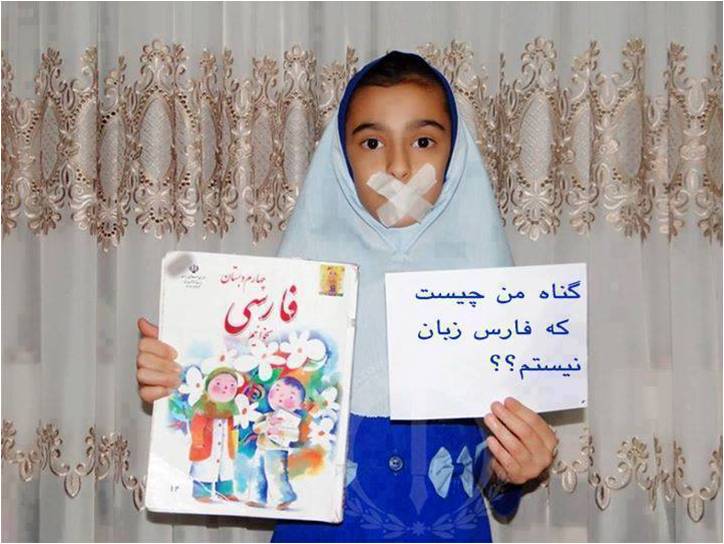

The call to teach ethnic languages also reached social networks (SNS), especially prior to UNESCO's International Mother Language Day, on February 21, 2014. A Facebook page dedicated to mother tongues was launched to collect Iranian media reports concerning this issue and follow the government’s implementation of its promises in this regard (mother language facebook page).

|

|

| “Is it a sin that I do not speak Farsi?"

Source: mother language facebook page |

The sensitive issue of minorities

The current public discourse concerning the teaching of local languages once again raised the issue of ethnic-linguistic minorities, which has been very sensitive in Iran for years. On a number of occasions ethnic tensions have even led to violent confrontations between minorities and the authorities. For example, in May 2006 riots broke out in Tabriz and other cities in the province of Azerbaijan, after the government newspaper "Iran" published a cartoon presenting an Azeri as a cockroach. Following the riots, the paper was closed down for several weeks. Ethnic tensions recently occurred again following a broadcast of a TV series that offended the Bakhtiari minority concentrated in southwestern Iran. The documentary series “Ancient Land” which was aired on state television, raised Bakhtiari citizens' ire by depicting a Bakhtiari family as collaborating with the British occupiers of Iran during World War II. After violent protests broke out in several cities in southwestern Iran, the series was cancelled (Tehran Times).

Despite criticism of its initiative, the government has not retreated from its intention to implement Article 15 of the Constitution. Presidential Advisor Ali Younesi has recently rejected the criticism stating that just as there is no problem teaching Arabic and English, there is no reason that learning the local languages, such as Kurdish and Azeri, would be a problem or detrimental to the status of Farsi (ISNA). However, the ability of the government to live up to its intention of allowing the teaching of ethnic languages in the educational system is questionable. The sensitivity of minority issues in Iran, the limitations imposed on the government by its right-wing conservative opponents and past experience indicate that government promises to promote the rights of minorities are unlikely to materialize. A large question mark hangs over the ability of Rouhani’s government to lead a significant change in the discriminating policy against minorities. It should be noted that Rouhani’s promise to integrate minorities into his government was not yet implemented, and it is possible that the promise to lift the restrictions on ethnic languages will probably remain unfulfilled as well■

* Dr. Raz Zimmt (PhD) is a research fellow at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

T h e A l l i a n c e C e n t e r f o r I r a n i a n S t u d i e s ( A C I S )

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

Iran Pulse No. 69 ● May 23, 2014

© All rights reserved