Previous Reviews

Number 83 ● January 29, 2018

The Recent Protests in Iran and the Cultural Revival of the Royal Past

Liora Hendelman-Baavur*

Brief videos taken during the recent protests in Iran, which erupted in Mashhad on December 28, and soon spread to other cities, show demonstrators chanting slogans sympathetic to the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, who was deposed in the 1979 Revolution, (VOA, December 30, 2017; Jihadwatch, December 30, 2017). Expressions of sympathy for the monarchy are unprecedented in public protests in the Islamic Republic. Rather than an aspiration to replace one autocratic regime with another, the implied signs of nostalgia for the Pahlavi dynasty are an additional expression of the cumulative dissatisfaction felt by different sectors in Iran on account of their current distressful circumstances.

While expressions of sympathy for the Shah are marginal and isolated phenomenon in the recent waves of protest, they echo a renewed interest in the pre-revolutionary royal era on the part of young people born after the establishment of the Islamic Republic. This interest is largely the result of increasing anti-Pahlavi propaganda sponsored by the regime in recent years. Anti-monarchist propaganda in the post-revolutionary era, including rewriting history in books, articles, etc., is primarily aimed at solidifying public support for the theocratic regime, and fostering the revolutionary fervor that has faded over the years. However, the reactions provoked by this propaganda, as revealed during the recent demonstrations, indicate its unexpected consequences.

In May 2003, the National Car Museum, sponsored by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization, was inaugurated in Karaj, near Tehran. The central exhibition displays a limited selection of the luxury fleet of vehicles belonging to Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his family. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Shah was known as an avid sports car enthusiast, and there were reports about his habit of testing their road performance on the outskirts of the capital. Many of the vehicles exhibited in the museum were custom-made, limited editions including the royal carriage built in Vienna for the coronation of the Shah and his wife in 1967.

During the 1979 revolution, some of the vehicles were damaged by revolutionary forces, others were spirited away from the palace, hidden, and saved by private initiatives of local car enthusiasts. During the 1990s, the sale of the remaining vehicles to a foreign buyer was thwarted at the last minute, and they received the status of protected items of the national cultural heritage.

Other than the National Car Museum, in the last decade, permanent exhibitions have been added to museums located in the complex of the Sa’dabad and Niavaran palaces (in northern Tehran) and the summer palace in Ramsar (on the shores of the Caspian Sea), and opened to the public. In conjunction with the project to restore the rooms, furniture, carpets, pictures and personal effects of the Pahlavis, extensive efforts were invested in the restoration and conservation of royal garments, including lavish dresses especially created by some of the 20th century most renowned western designers, for the royal women to wear on special occasions. For example, in 1959 the wedding gown worn by Farah Pahlavi, Mohammad Reza Shah’s third wife, was reported to be the most expensive dress made by that time (The Age, December 22, 1959). Designed in the late 1950s by Yves Saint-Laurent, it continues to inspire haute couture to this day (Sa’dabad Museum, June 19, 2017).

The restored dressing room of Farah Pahlavi at the Niavaran Palace, Tehran

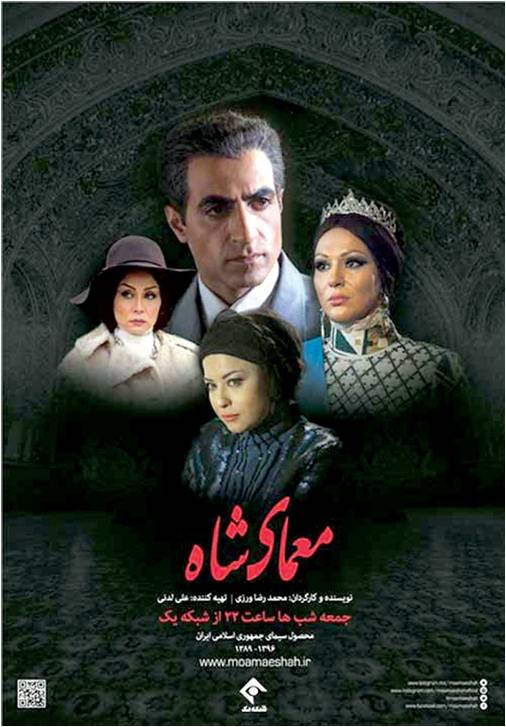

An even more tangible expression of the renewed pre-occupation with the Pahlavi royal family is the historical television series, “The Enigma of the Shah” (Mo'ammāye Shāh, 2015), and the public debate it stimulated (The Arab Weekly, February 19, 2016). The series recounted the history of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, from his first marriage to Egyptian Princess Fawzia in 1939,covered the circumstances that led to his ascension to power after an Anglo-Soviet invasion forced the abdication of his father in 1941, and continued until the overthrow of his regime four decades later.

Press reviews prior to its release raised great expectations for the series, but they fell short after the first episodes were aired. A host of errors, such as the attribution of a poem written in recent years to the pre-revolutionary era, and casting an older actor to play a much younger character, generated ridicule and antagonism among viewers who responded on social networks. Culture critics did not spare their criticism, and decried the implausible dialogues presented in the series, the repetitious use of slogans and clichés (e.g., “There is no blessing for a city ruled by a dictator”) and the distortion of historical narrative to fit the regime's propaganda, which is inconsistent with the standards and reality of younger Iranians (see Mehrnews.com, December 12, 2016). Criticism was also voiced by clerics like Hujjat al-Islam Shahab Moradi who questioned, in a television interview, the series’ portrayal of the Shah as a weak leader with dubious sexual tendencies. Moradi emphasized the Shah was a cruel dictator who enjoyed the support of the entire world until Ayatollah Khomeini's greatness led to his defeat (fararu.com, January 13, 2016).

Poster advertising the television series, “The Enigma of the Shah” (2015)

A contemporary cultural revival of the royal past through television and film productions, the publication of historical books and exhibitions dedicated to the local monarchy is also found in other Middle Eastern countries. In Turkey, longing for the golden age of the Ottoman Empire increased after the victory of the Islamic Justice and Development Party, led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in the 2002 elections, and against the backdrop of deepening social crisis and economic collapse that led to a massive wave of layoffs in the Turkish economy (AGOS, May 25, 2016). In Egypt, there were those who identified rising interest in the era of King Farouk with the economic crisis of 2007-8 that caused a dramatic spike in prices of basic foodstuffs, leading to strikes and riots in various parts of the country(The Guardian, June 10, 2010, Tel Aviv Notes, March 14, 2017).

In the Islamic Republic, the increasing preoccupation with the royal past under the aegis of the theocratic regime was intended to present the flamboyant, hedonistic, and corrupting lifestyle of the Pahlavis to a generation that did not know the Shah, thereby granting renewed justification to the Islamic Revolution that had ousted him from power. In addition, the above mentioned museums and the collection of western art purchased by the royal family, including paintings by Renoir, Matisse, Degas, Picasso, Warhol and Pollock, are valuable economic assets for Iran with considerable potential for attracting future tourism.

For almost three decades, this collection of artworks, considered by the revolutionary regime epitome of western imperialism and the royal family's involvement in the suppression of Iran by decadent, immoral culture and exploitative capitalism, was relegated to basements. Despite local objections, as of the late 1990s selected works from the collection are being displayed in temporary exhibitions of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran (New York Post, May 28, 2017).

Public expressions of nostalgia for the monarchy in general and for the Pahlavis in particular were voiced, until recent years, almost exclusively by pro-royalist groups or individuals who fled the horrors of the revolution in the late-1970s and are now living in exile. While for many exiles, the yearning for the royal family preserves their connection with the homeland and their longing to return, the Islamic Republic strives to systematically and decisively delegitimize the Pahlavi dynasty. In March 1999, the Revolutionary Court ordered the immediate closure of the women’s daily Zan (“The Woman”) after it published Farah Pahlavi's greetings to the Iranian people upon the Persian New Year.

Fifteen years later, against the backdrop of the nuclear agreement between Iran and the superpowers, and mounting predictions about lifting the economic sanctions of Islamic Republic, a completely different picture has emerged. In a series of articles published in 2015, the local correspondent of The Guardian reported that the large markets in major cities freely offered a wide range of royal souvenirs and vintage items commemorating the Pahlavi royal family. It also emphasized that there were more local visitors at the royal palace in Sa’dabad than at tomb of Ayatollah Khomeini, on the 36thanniversary of his return from exile (The Guardian, February 9, 2015). Interviews with young urbanites included positive statements about the deposed Shah and his family, and even some overt sympathy (The Guardian, June 17, 2015).

A similar trend was also reflected in the reactions to the documentary “From Tehran to Cairo” by Iranian viewers at home and abroad. The film, based on a series of interviews with Farah Pahlavi (b.1937), was first aired in 2012 by the Manoto satellite channel that broadcasts from London in Farsi. The historical distance from the royal era, and especially the deaths of two of her four children with the Shah during the first decade of the 21st century, stimulated more than a few personal remarks expressing sympathy, sorrow or forgiveness towards the former Empress of Iran (Economist, August 22, 2012).

Although it is difficult to draw unequivocal conclusions about the long-term implications of the recent waves of protest in Iran, the slogans sympathetic to the Shah that were voiced by some of the demonstrators were hardly accidental. Their implied nostalgia for the pre-revolutionary era reflects on the dimensions of current social indignation, highlighting the severity and extent of Iran’s economic circumstances, and social and political problems. The Shah is not an actor in the political system of the Islamic Republic, and the mere mention of his name implies a blatant defiance of both the conservative and reformist camps in Iranian politics, which have failed to fulfill their promises to the public in the last twenty years, especially those concerning the economy.

The connection between economic crisis and cultural revival of the royal past, whether as a real political option, nostalgia or even an aesthetic experience and notion of a good life, is a phenomenon that goes beyond Iran. Against the background of the global economic crisis of 2008, similar signs were found beyond the Middle East: in post-socialist Romania, Bulgaria and Serbia, as well as Spain, Portugal and France. However, in the specific context of the recent demonstrations in the Islamic Republic, this global trend has a unique political dimension. The cultural revival of Iran's royal past by the regime itself, generated unexpected reactions that undermine its revolutionary aims.

* Dr. Liora Hendelman-Baavur is a senior research associate at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies at Tel Aviv University.

Tel Aviv University, Ramat-Aviv 61390, Tel Aviv P.O.B. 39040, Israel

Email: IranCen@post.tau.ac.il , Phone: +972-3-640-9510

F a x : + 9 7 2 - 3 - 6 4 0 - 6 6 6 5

ACIS Iran Pulse No. 83 ● January 29, 2018

©All rights reserved